As you’ve watched Kansas City Ballet dance to beautiful music played by Kansas City Symphony and led by Kansas City Ballet Music Director Ramona Pansegrau, you may not have given much thought to just how the music gets played. And that’s because Ms. Pansegrau has been working intently behind the scenes—sometimes for years before a piece is performed.

Nearly everyone has seen sheet music before and as you read the first paragraph, perhaps you even pictured it in your head. Pristine pages with notes that will all be played. But in reality, those sheets of paper have been pored over by numerous folks before they are ever performed for ballet. That’s because when working with a symphony there are so many parts that must be dissected and notations that must be added.

Let’s back up for a minute. When a choreographer selects a piece of music to create a dance to, a lot of things happen. First of all, rights and royalties must be secured for the music from the composer and publisher, including grand rights for performances, and also rental of the physical music. Choreographers can have a lot of leeway. Perhaps they want to edit the score to fit their vision, possibly removing certain phrases or adding in repeats. All of this affects the score—and ultimately any other music director with any other dance company looking to perform the piece again later. Because, you see, just having an agreement to use the ballet, doesn’t mean you’ll get “ready to play” music with it. You may need to recreate your own.

Behind the scenes, music directors like Ms. Pansegrau are often having to recreate the pieces, pull out the separate parts for the orchestra sections, make bowing marks (how to play the notes for stringed instruments), and mark up how to play the notes for the dancers so that the dance and the music are one.

As Ms. Pansegrau explains, “For some world premiere ballets, only one copy of the marked score exists and it’s not usually shared. A score with no markings can be overwhelming. Even when we are doing pieces that have been done before, by other companies, we can be expected to figure out the music on our own, using video or choreographer’s notes, etc.”

That’s where having personal relationships and history on your side is a real asset. “Last fall, we performed the Mendelsohn music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Boston Ballet hadn’t performed it for 20 years—since I was there—but they dug in a warehouse to find the old set of parts. And, in exchange, we shared a marked set of parts we had to a Peter Martins’ ballet they were performing,” she said.

Notes and markings save so much time and effort that could be channeled into better things rather than recreating the wheel. A marked set of parts is like gold for a music director and a ballet company.

“We traded for the marked and arranged music for Jerome Robbins The Concert set to Chopin from Pittsburgh Ballet because we let them use our copies of music for Lynn Taylor-Corbett’s Great Galloping Gottschalk set to music by Louis Moreau Gottschalk.”

Creating an atmosphere of change locally, has benefited both the ballet and the symphony. A while back, the ballet performed a piece to the adagietto from Mahler’s 5th symphony. Since then KCS’s Music Director Michael Stern borrowed the marked version from the ballet since it was bowed and marked by their own musicians—saving them time and effort recreating the wheel. And, the ballet used KCS’s Dvořák 9th symphony score on last spring’s repertory performances. Trades like this have been great for our relationship.

But there are still other challenges for music: In the spring of 2015, Kansas City Ballet performed Wunderland by Edwaard Liang. Wunderland was originally set to a string quartet, but Ms. Pansegrau adjusted it so that it worked for the entire string section of the orchestra. In the process, the various movements from various works that Liang used had to be collated and made into a single part for each orchestra player. She also had to piece together music that has been only performed to a recording for other ballet companies but we want to use live musicians. And, she’s even had to become a true music detective to piece together music for ballets that are so old no one living knew just how they sounded—which was the case for Frescoes (from The Little Humpbacked Horse) by Arthur Saint-Léon set to Cesare Pugni’s music that the ballet performed in the fall of 2009. For that particular work, she wrote out the music note by note for every part in the orchestra and then used a computer music writing program to make the complete set of parts.

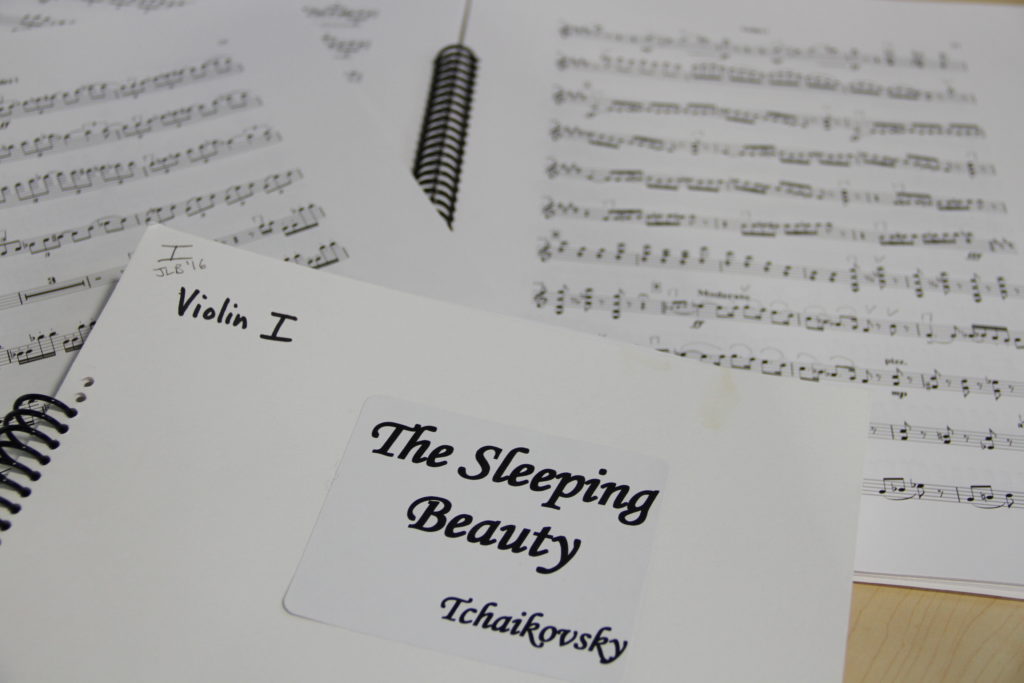

One of the most famous ballets in the world—Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker—varies by company. For many musicians who’d been using the same music binder for years, the idea of having to start over for the Ballet’s recent new production was too much to bear. So instead, Ms. Pansegrau edited the old parts to adjust to the new version of the ballet. That way they still had much of their broken-in old friend in-tact. “They know where on the page their parts begin. Sometimes it’s the littlest things that are the hardest to change,” says Ms. Pansegrau. “We all are creatures of habit.” Currently, Ms. Pansegrau is working on a brand new set of parts for our premiere of The Sleeping Beauty. “I started on them in February of 2016—I think I’m going to make it, but just barely.”

“It’s hard to believe when I started at here in KC they gave me two cardboard boxes of music—the full breadth of our music library—and now I have this!”

Since she began, Ms. Pansegrau has worked to document and save the music for works the company has performed. There have been many labors of love that have taken up to two years to prepare all of the parts and binders for the musicians. “I’m saving all my work so that I and others don’t have to start from scratch again. Our growing music library is a true resource for the company and an asset for the future.”

Bless her!